|

Object

A Woman’s Work: Surrealist Artist Meret Oppenheim

In 1924, with the West on the mend after World War I, French poet André Breton unleashed a manifesto of a brand-new revolution: the artistic, intellectual, and literary movement known as Surrealism. From this point, until the end of World War II, the artists, writers, and intellectuals who joined Breton sought to creatively undermine what they viewed as postwar society’s excessive rationality and oppressive order. They accomplished this by producing work generated not out of the conscious—that cerebral, rule-bound part of the mind—but by tapping into the unconscious, its desiring, dreaming, irrational portion. “Beloved imagination,” Breton wrote in his manifesto, “what I most like in you is your unsparing quality.”

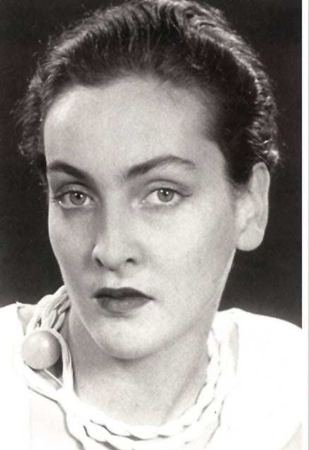

Women were largely regarded as the subjects and muses of the men who dominated Surrealism, among them Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Man Ray, and René Magritte. So, it is notable that painter and sculptor Meret Oppenheim (German-Swiss, 1913–1985) made a place for herself as one of Surrealism’s central artists and produced some of its most powerful works. In 1932, she moved to Paris, the center of the movement, and was soon participating actively in their meetings and exhibitions. By 1936, she had her first solo exhibition. Assuming she, like her artistic peers, must be male, critics and admirers of her work often mistakenly referred to her as “Mr. Oppenheim.”

The artist possessed a wry wit and was keenly aware of how women were regarded by both the Surrealists and society. Suffused with humor, eroticism, and menacing darkness, her work reflected her critical explorations of female sexuality, identity, and exploitation. Oppenheim became known for her assemblages, sculptural works in which she brought everyday, often domestic, items into disturbing and humorous juxtaposition. For the Surrealists, such objects served to crack the veneer of civilized society, revealing the sexual, psychological, and emotional drives burning just beneath the surface.

A Sensational Teacup: Meret Oppenheim’s Object (1936)

It began with a joke over lunch. In 1936, Meret Oppenheim was at a Paris café with Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso, who noticed the fur-lined, polished metal bracelet she was wearing and joked that anything could be covered with fur. “Even this cup and saucer,” Oppenheim replied and, carrying the merriment further, called out, “Waiter, a little more fur!” Her devilish imagination duly sparked, the artist went to a department store not long after this meal, bought a white teacup, saucer, and spoon, wrapped them in the speckled tan fur of a Chinese gazelle, and titled this ensemble Object. In doing so, she transformed items traditionally associated with decorum and feminine refinement into a confounding Surrealist sculpture. Object exemplifies the poet and founder of Surrealism André Breton’s argument that mundane things presented in unexpected ways had the power to challenge reason, to urge the inhibited and uninitiated (that is, the rest of society) to connect to their subconscious—whether they were ready for it or, more likely, not.

While Oppenheim was not the only artist bringing everyday things into unlikely alliance in the 1930s, her fur-covered teacup is considered to be among the quintessential Surrealist objects. It caused a sensation when it was introduced to the public in 1936, first in Paris, at the inaugural exhibition of Surrealist objects organized by Breton, and then in New York, at The Museum of Modern Art’s show Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism. “The fur-lined-cup school of art,” ran a headline of the day, capturing the mixture of bemusement, offense, shock, and fascination Object provoked. Though many viewers could not comprehend how or why it constituted a work of art, by 1946, The Museum of Modern Art acquired the work.

“Art […] has to do with spirit, not with decoration,” Oppenheim once wrote, and a work as small and economical as Object has such outsized spirit because fur combined with a teacup evokes such a surprising mix of messages and associations. The fur may remind viewers of wild animals and nature, while the teacup could suggest manners and civilization. With its pelt, the teacup becomes soft, rounded, and highly tactile. It seems attractive to the touch, if not, on the other hand, to the taste: Imagine drinking from it, and the physical sensation of wet fur filling the mouth.

Source here.